On Thursday the Blue Jays acquired Nick Kingham, a 27-year old right-handed pitcher. The former 4th round draft pick spent the past nine years in the Pirates system. Kingham was out of options and the Pirates needed to make a roster move. Desperate for reinforcements on the mound, the Jays swooped in and worked out a trade for cash considerations. It’s a low risk move with the potential for a good payoff.

You might remember his Major League debut last year when he took a perfect game into the 7th inning against a strong Cardinals lineup.

It was an impressive beginning to his career but things quickly went downhill. He gave up three or more runs in seven of his next 10 starts for a 5.43 ERA in that stretch. The Pirates moved him to the bullpen where he’s remained a multi-inning guy in 2019, with the occasional start. Since May, Kingham has pitched to a 12.21 ERA and a slightly better, but still atrocious, 6.15 FIP.

His career ERA sits at 6.67 across 32 games, 19 of which are starts.

Without options remaining, the team designated him for assignment knowing they might lose him to another club. They did, and now it’s the Blue Jays’ turn to try and resurrect a once-promising career.

So what does Ross Atkins and Co. see in Kingham? They’ve been desperate enough to run Edwin Jackson out there every fifth day despite an ERA over 10 so this appears to be another shot in the dark. But I believe Kingham has real upside, with the proper changes. And the Jays might want to start by looking at his fastball usage.

His Four-Seam Fastball Is Bad

Like, really bad. His four-seamer averages 92.3 mph and it’s the pitch he uses most often at 37%.

Its 15.4% whiff/swing rate sits at a lowly 20th percentile rank of 166 starting pitchers who have thrown at least 100 fastballs this year. It also results in more fly balls than average. Hitters have teed off on the four-seamer, to a .392/.475/.627 triple slash line. He can’t expect to have success with a primary pitch like that.

But maybe there’s hope. His four-seamers in 2018 resulted in an opposition batting average of almost 150 points lower, at .243. He was also walking fewer hitters with it and striking more out.

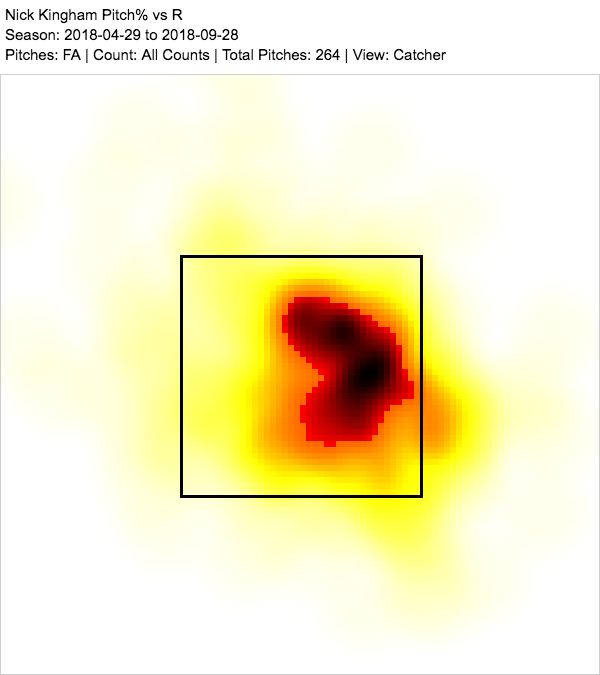

Heat maps from his two seasons show a change in location. Lets focus on right-handed batters. The first image is from 2018, from the catcher’s point of view.

Kingham generally worked righties away, going up and down as needed. That’s changed in 2019.

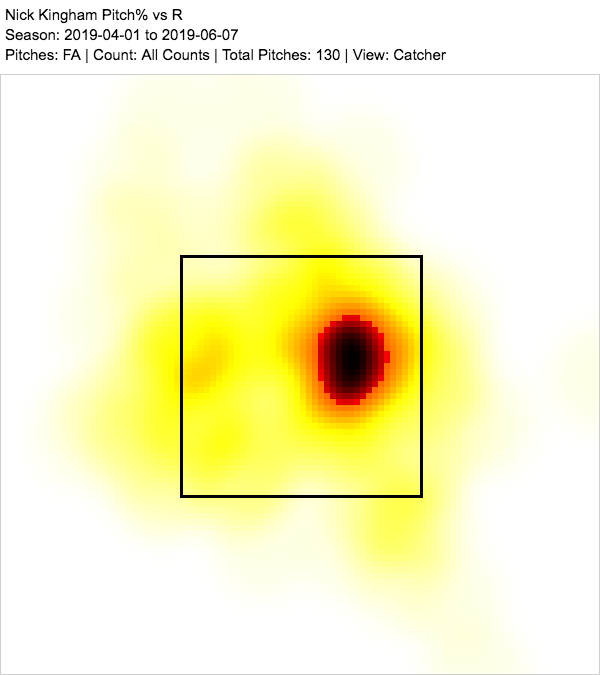

It looks like he still has the same mindset as he did in 2018 but isn’t locating near the edges of the zone as much. And a zone breakdown of swing and miss from the four-seamer shows why that’s important.

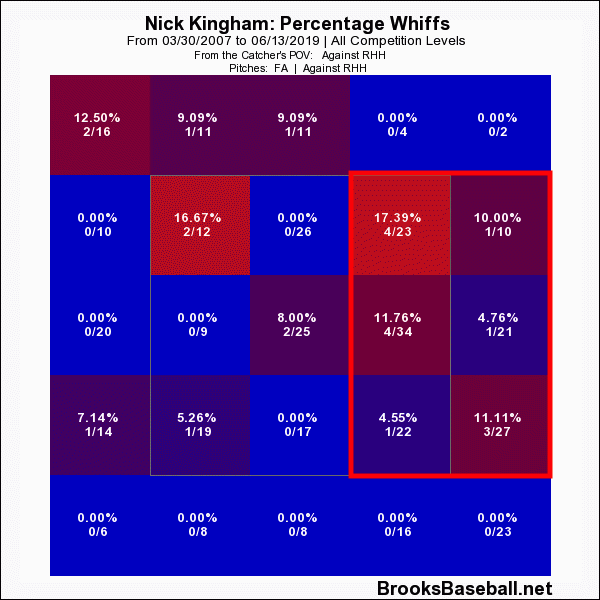

Again, this is from the catcher’s point of view. The red outline highlights the outer third of the strike zone and the area out of the zone away to right-handed hitters. Four of those six smaller zones have a whiff rate of over 10%.

The 2019 heat map shows that he’s not throwing to those zones as much – the zones where he gets the most swings and misses. It could be a mechanical issue. There’s nothing glaring in the Statcast data but his release point has changed slightly (towards his glove side by about two inches) and the shape of the pitch is different. He’s getting less horizontal movement and more vertical drop. With an average velocity of just 92 mph he probably wants more “rise” on the four-seamer, not more drop.

The Two-Seam Fastball Is Even Worse

The sinker’s getting rocked too, to a Bonds-like .400/.500/.733 triple slash. What is traditionally a pitch that generates ground balls, in fact does the opposite.

It averages 90.5 mph and generates a 36% ground ball rate (which are 18th and 4th percentile ranks respectively). So why in the world is he throwing such a horrible pitch? The answer: the Pirates.

The trend across baseball of throwing fewer two-seamers never made it to Pittsburgh. With batters making swing adjustments to generate better contact on sinkers, throwing fewer of them makes sense. But where others zigged, the Pirates zagged. Sometimes a team can find an inefficiency by doing things differently than the crowd, and they’ve seen success from preaching sinkers in the past. But a few recent examples have not enjoyed the same results.

Tyler Glasnow experimented with a sinker in 2017 and it was his worst pitch that year by some metrics. He’s not throwing any now as a member of the Rays and when healthy he’s looked like a Cy Young candidate.

Chris Archer scrapped his sinker in 2014 as a member of the Rays, opting for more four-seamers. He went on to post three-straight 200-inning seasons with almost 13 WAR. But now he resides in Pittsburgh and, predictably, the Pirates have him throwing sinkers again. His 5.06 ERA and 5.14 FIP suggests that the plan was flawed.

Now that Kingham’s in a different organization will his pitch repertoire change? Time will tell. The Blue Jays do employ Aaron Sanchez and Marcus Stroman, who throw more sinkers than only 11 other qualified pitchers. But I’m hoping the Jays don’t take Pittsburgh’s “one size fits all” approach with Kingham.

He also throws a cutter at 90.7 mph that has almost as much horizontal break as his slider. Could this be something he uses more in lieu of the sinker?

His changeup was a weapon last year that generated a high number of swinging strikes. It hasn’t been as good this year but maybe sequencing it differently would help. In 2018 he paired a 1st pitch four-seamer and 2nd pitch changeup 41 times to left-handed hitters. This year he’s sequenced those to lefties only twice. Marco Estrada showed how effective that combo can be during his tenure in Toronto.

Whichever tactics the Jays employ, it’s obvious that Kingham needs to attack hitters differently. I don’t think Pittsburgh’s sinker-centric philosophy did him any favours and I’m optimistic about a rebound in Toronto. Going into 2014, he ranked 64th on Baseball America’s Top 100 prospects list and 58th on MLB Pipeline. The pedigree was there.

He still has a six-pitch mix, and he’s not even arbitration eligible for another two seasons. The Blue Jays have shown they have the stomach for reclamation projects at this stage of their rebuild. Will it work out in Toronto where it didn’t in Pittsburgh? Who knows, but it can’t get any worse.